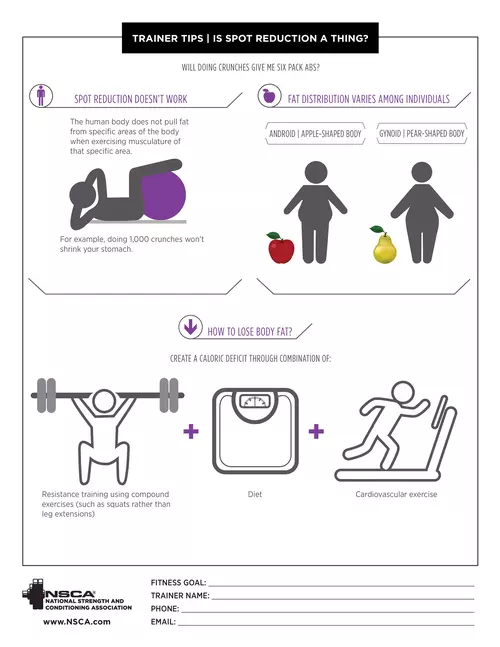

HOW TO LOSE BODY FAT? SPOT REDUCTION DOESN'T WORK

Scoring a flat stomach is all about workouts that burn body fat overall. One of the best ways to do that is utilizing exercises that are core focused,

adsPart of the document

FITNESS GOAL:

TRAINER NAME

:

PHONE:

EMAIL:

www.NSCA.comTRAINER TIPS | IS SPOT REDUCTION A THING?

HOW TO LOSE BODY FAT?

The human body does not pull fat

from specific areas of the body

when exercising musculature of

that specific area.

For example, doing 1,000 crunches won't

shrink your stomach.

CREATE A CALORIC DEFICIT THROUGH COMBINATION OF:GYNOID | PEAR-SHAPED BODY

ANDROID | APPLE-SHAPED BODYResistance training using compound exercises (such as squats rather than

leg extensions)Cardiovascular exerciseDiet

SPOT REDUCTION DOESN'T WORKFAT DISTRIBUTION VARIES AMONG INDIVIDUALS

WILL DOING CRUNCHES GIVE ME SIX PACK ABS?

www.NSCA.com

TRAINER TIPS | IS SPOT REDUCTION A THING?

WHAT IS SPOT REDUCTION?

C

ontrary to popular belief, the human body does not pull fat from

specific areas of the body when exercising the musculature of

that specific area. Marketing and misinformation about "spot

reduction" can be misleading. Clients looking for fat loss should

focus on compound movements that involve high levels of muscle

recruitment, which increases energy expenditure to a greater extent.

DISPELLING THE MYTH

While exercises that target specific areas of the body (such as

crunches and the abdominal region) can utilize intramuscular fat as

an energy source, they do not isolate and oxidize subcutaneous fat

in that area preferentially. Intramuscular fat is a fuel source stored

within muscle and, unlike subcutaneous fat, has no influence on health

or appearance (Schoenfeld, 2011). A 2011 study looked at the e?ects

of core exercises on abdominal fat for groups doing seven di?erent

abdominal exercises versus those who did not. Taking into account

all other factors, there was no significant di?erence in abdominal

subcutaneous fat at the end of those 6 weeks between the groups,

showing that regional exercises do not impact the subcutaneous fat

in that area (Vispute, et al., 2011). Another study performed in 2013

found that 12 weeks of training only the non-dominant leg resulted in

reduced fat mass in the trunk and arms but showed no change in lean

mass, fat mass, or fat percentage in either leg (Ramirex-Campillo, et

al., 2013).

GENETICS AND REGIONAL FAT LOSS

An individual's bodyweight is the result of a number of factors

including genetic, metabolic, behavioral, environmental, cultural,

and socioeconomic influences. In addition, there are two types of fat

distribution; gynoid (pear-shaped body) and android (apple-shaped

body). An individual with a gynoid body type tends to store fat in

the hip and thigh areas while android body types tend to store fat in

the trunk and abdominal regions (Smith, et al., 2012). The take home

message here is that bodyweight and fat distribution throughout the

body is multi-factorial; each individual client will gain and lose body

weight from various body areas despite focus on a specific region of

the body during training.

MAXIMIZING FAT LOSS

A negative calorie balance is required for net weight loss, meaning

an individual needs to utilize more calories than what is consumed

on a daily basis. While this can be accomplished through dietary

changes alone, it seems prudent to include resistance training (RT)

to increase lean body mass (and subsequently increase or maintain

resting metabolic rate) as well as cardiovascular training to increase

caloric expenditure.

It has been well established that RT leads to favorable changes in

muscle mass and body composition as well as strength, muscular

endurance, bone density, cardiac risk factors, psychosocial well-being,

and metabolism (Sword, 2012). Given that the greater the amount of

muscle mass involved in a workout results in a greater total caloric

expenditure (as well as other positive systemic hormonal responses), it appears beneficial to emphasize total body, compound exercises (e.g.,

squats) over isolated exercises (e.g., leg extension) for clients seeking

to improve their body composition.

The health-related benefits associated with aerobic exercise include

enhanced insulin sensitivity, reduced body fat, increased bone

mineral density, as well as improved cardiovascular and respiratory

function (McCarthy, et al., 2012). Moderate-intensity steady state

aerobic exercise utilizes a greater percentage of fat oxidation to fuel

performance compared to high-intensity interval training (HIIT).

However, research suggests that HIIT is superior to steady state

aerobic exercise for improving body composition, VO

2

max, insulin

signaling, and blood pressure (Schoenfeld, et al., 2009).

Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) di?ers from structured

physical activity and encompasses all of the energy expended from

activity outside of exercise and normal bodily processes. In simple

terms, it refers to how much someone is moving on a daily basis

and can contribute to overall daily caloric expenditure. Examples of

NEAT include everything from walking to the car and taking the stairs

(instead of the elevator) to gardening and even shivering. Therefore,

it may be helpful to encourage clients to increase daily caloric

expenditure/lose weight to be more active throughout the day.

REFERENCES

1.

McCarthy, J., & Roy, J. (2012). Physiological Responses and

Adaptations to Aerobic Endurance Training. In M. Malek, & J.

Coburn,

NSCA's Essentials of Personal Training

(2nd ed., pp. 89-106).

Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

2.

Ramirex-Campillo, R., Andrade, D., Campos-Jara, C., Henriquez-

Olguin, C., Alvarez-Lepin, C., & Izquierdo, M. (2013, August). Regional

Fat Changes Induced by Localized Muscle Endurance Resistance

Training.

Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research

, 27(8), 2219-

2224.

3.

Schoenfeld, B. (2011, February). Does Cardio After an Overnight

Fast Maximize Fat Loss?

Strength and Conditioning Journal

, 33 (1),

23-25.

4.

Schoenfeld, B., & Dawes, J. (2009, December). High-Intensity

Interval Training: Applications for General Fitness Training.

Strength

and Conditioning Journal

, 31 (6), 44-46.

5.

Smith, D., & Fiddler, R. (2012). Clients With Nutritional and

Metabolic Concerns. In J. Coburn, & M. Malek,

NSCA's Essentials of

Personal Training

(2nd ed., pp. 489-519). Champaign, IL: Human

Kinetics.

6.

Sword, D. (2012, October). Exercise as a Management Stretegy

for the Overweight and Obese: Where Does Resistance Exercise Fit in?

Strength and Conditioning Journal

, 34 (5), 47-55.

7. Vispute, S., Smith, J., LeCheminant, J., & Hurley, K. (2011,

September). The E?ect of Abdominal Exercise on Abdominal Fat.

Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research

, 25 (9), 2559-2564.